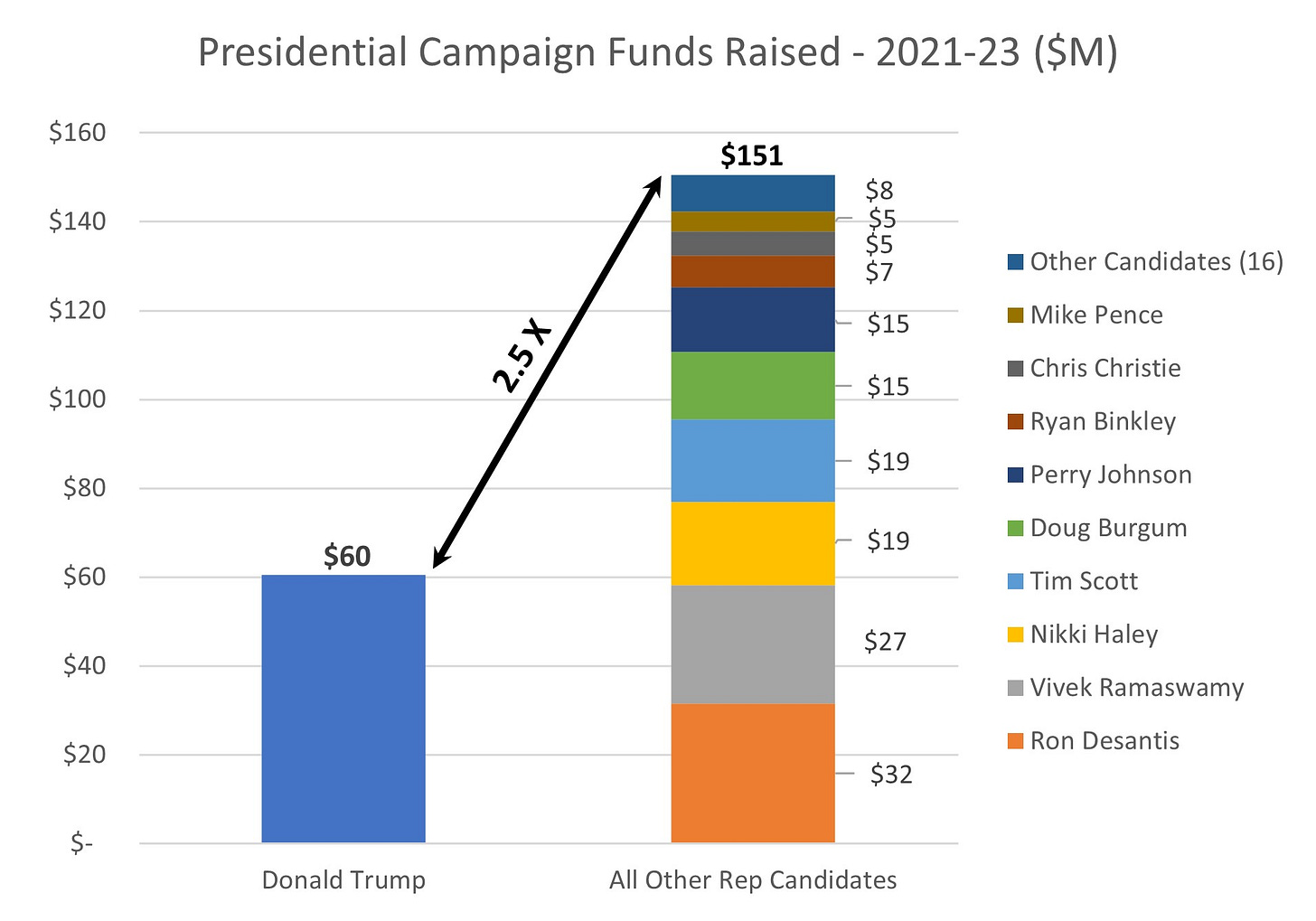

For Republicans, the 2024 election, like the 2020 election, has always been a numbers game. Former President Trump has a strong base in the party, and all the other Republican candidates have been competing for the rest of the party’s votes. This has resulted in predictable outcomes: Trump has refused to participate in party debates and has watched his competitors beat each other up as he remains above the fray. This pattern is very clear in fund-raising. The following chart shows campaign funds raised by Republican presidential candidates from 2021-23, according to the Federal Elections Commission:

While Trump has raised $60 million, his competitors have raised over $150 million from Republican donors. (Some of the candidates - e.g., Ramaswamy and Burgum - self-funded a large portion of their campaigns.)

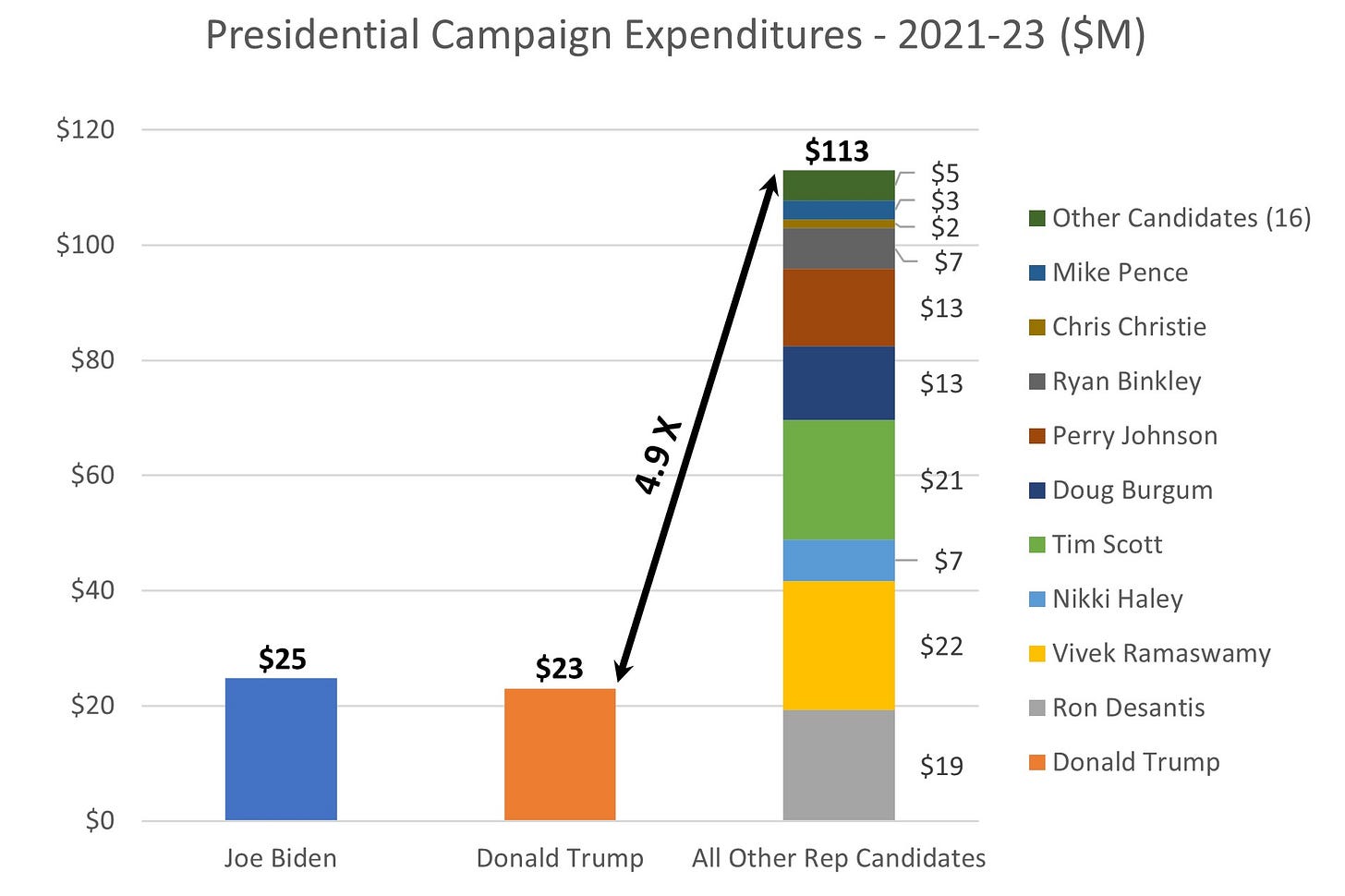

On the expenditures side, the picture is even more skewed:

Trump’s Republican competitors have spent almost five times as much Trump’s campaign, which itself has kept pace with President Joe Biden’s campaign expenditures. This is completely understandable, since the non-Trump Republicans have been competing with each other in the important early-primary state races - Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina.

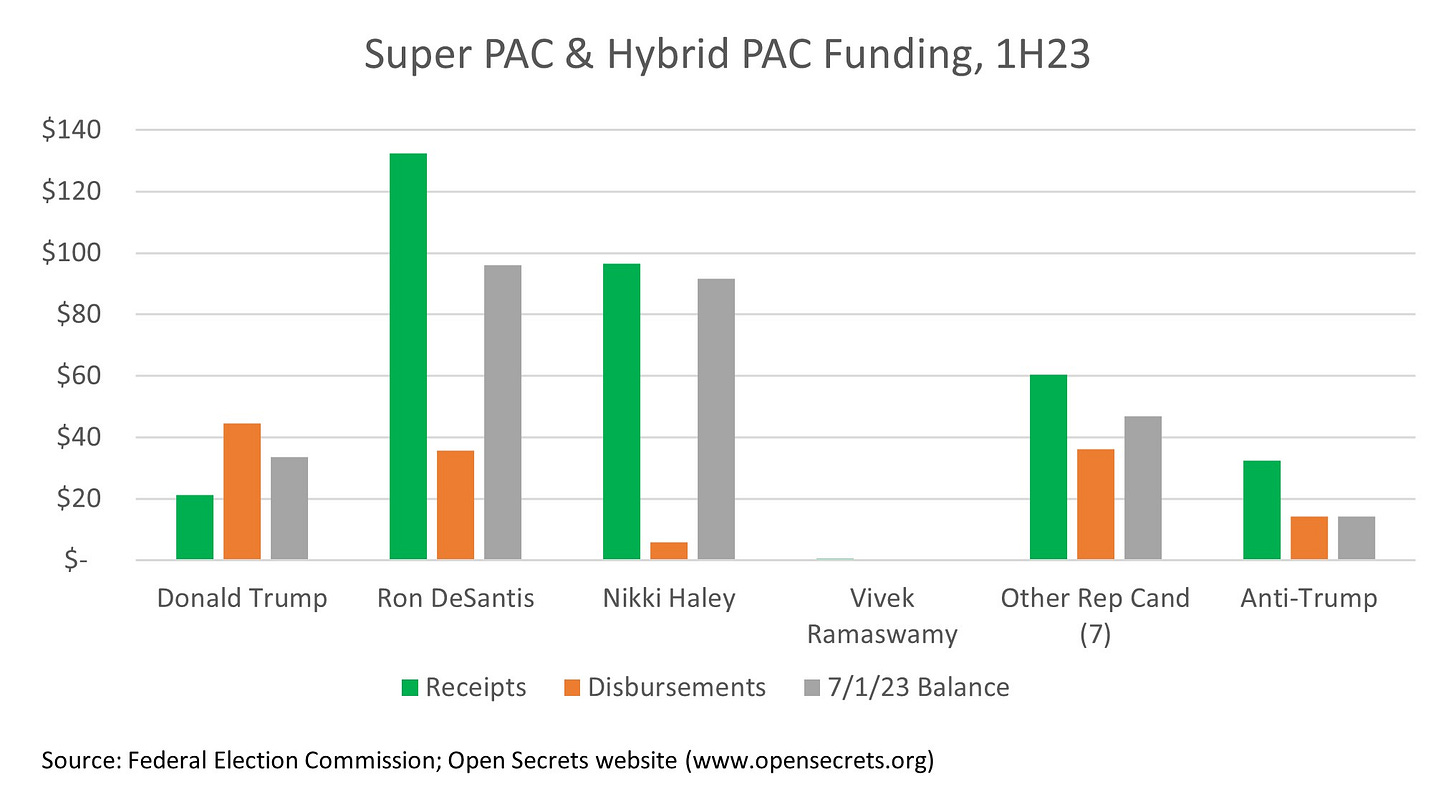

Of course, direct campaign funding is only part of the story. The candidates also rely on allied Super PACs and Hybrid PACs such as Make American Great Again, Inc. (Trump) and Never Back Down, Inc. (DeSantis) to fund many critical campaign activities - direct mail, ad production and media buys, social media placements, etc. In fact, the amount of money raised and spent by PACs is much greater than the amounts raised and spent directly by the campaigns. Here are the receipts and disbursements by Republican PACs by leading candidates for the first half of 2023:

One interesting feature of this campaign is that several PACs - Win It Back PAC, Club for Growth Action, and Liz Cheney’s The Great Task PAC - are funding opposition advertising against Trump, without necessarily advocating for a particular candidate.

Unfortunately, the Federal Elections Commission will not release 2H23 data for several weeks, but we know these PACs collected and disbursed substantial amounts in the second half of the year. For example, Vivek Ramaswamy’s PAC, American Exceptionalism PAC, which was late to the game, disbursed at least $6 million in the second half of the year.

Return on Campaign Investments

The return on investment for non-Trump candidates and their contributors so far has been nil. Here are Republican candidates’ poll numbers through the year, according to the 538 Project:

Campaign spending is an important driver, but it is not the whole story. The legal cases brought against Trump, principally by liberal district attorneys, have added to his advantage by:

Keeping Trump’s name front and center in the news, substituting unpaid publicity for campaign expenditures.

Making it difficult for competitors to criticize him without inviting charges of disloyalty and “supporting two-tiered justice” from the Republican base. Of all the Republican candidates, only Christie has taken a gloves-off approach to attacking Trump; all the others have supported Trump’s legal positions and soft-pedaled criticism to avoid enraging his base.

A Path for Trump Competitors: Merger

At this point, from an objective viewpoint, Trump’s momentum looks insurmountable. Polls in the early-primary states favor Trump, and even a breakthrough performance by Haley (possible) or DeSantis (less likely) will probably not change the trajectory of the primary contest.

However, there is one potential game-changing strategy that could defeat Trump for the Republican nomination, and it’s the same strategy that corporations often adopt when facing a dominant rival. If the two leading non-Trump Republicans, Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis, merged their campaigns, they would have a fighting chance to take the nomination away from Donald Trump. In addition to combining their existing war chests ($20-30 million in surplus campaign funds and $100-200 million in PAC funds, compared with Trump’s $70-100 million), such a merger could attract additional funds from Republicans and independents who would like to see an alternative to a Biden-Trump rematch - about 70% of the country, according to many polls.

Merging two presidential campaigns would face many obstacles, starting with deciding who would run for President. Making a deal would require the person who agrees to be Vice President to curtail his or her ambition in order to achieve a greater good for themselves and the country. It would require a commitment by the Presidential candidate to delegate important areas of responsibility and control to the Vice President beyond those specified in the Constitution. It would require creating a culture of teamwork within the administration - the opposite of a “tough guy” leadership style. Above all, it would require trust between the two principals and a commitment to collaborative policy-making.

These are serious challenges, but corporate leaders frequently work them out to the benefit of their owners and customers. In one merger between competing health systems, the two CEOs agreed that one would become CEO for the first five years and then turn it over to the other CEO for the next five years. It worked out just this way, and the combined system was immeasurably stronger.

Merging political campaigns also has precedents. In 1997, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown of Great Britain’s Labour Party reportedly agreed to a similar deal (the “Granita pact,” named after the restaurant in north London where it was supposedly hammered out). Blair would run for Prime Minister, and Brown would be appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, with expanded powers over much of the country’s domestic policies. The deal called for Blair to step down at the end of two terms and support Brown for Prime Minister.

The Granita pact produced a landslide victory for “New Labour” in 1997, with Labour gaining 132 seats and the Conservatives losing 159 seats in Parliament. The succession of Brown to Prime Minister eventually occurred in 2007, later than Brown was promised. Blair’s reluctance to turn over the reins is a cautionary tale because it heightened tensions within the Labour Party, which, combined with the Great Recession of 2008-9, caused Labour to lose to a Conservative-led coalition in 2010, and Brown was replaced by David Cameron.

Both DeSantis and Haley have considerable strengths as politicians and as experienced governors of large states. They share many policy positions and appear to have complementary strengths and sources of political support. If anyone can make a political merger work, it might be the two of them.

On the other hand, this competitive primary campaign has sharpened their criticism of each other, and they reportedly are not friends. Competition between corporations also has this effect, and competitive CEOs are rarely close, either. In the corporate world, Board members sometimes step up and help their CEOs see the broader vision and potential benefit of mergers. For politicians who don’t have Boards, perhaps major funders could play this role.