The federal government paid Americans almost $3.6 trillion in benefits in 2023, 36% more than in 2019. Eight entitlement programs accounted for over $3 trillion of this:

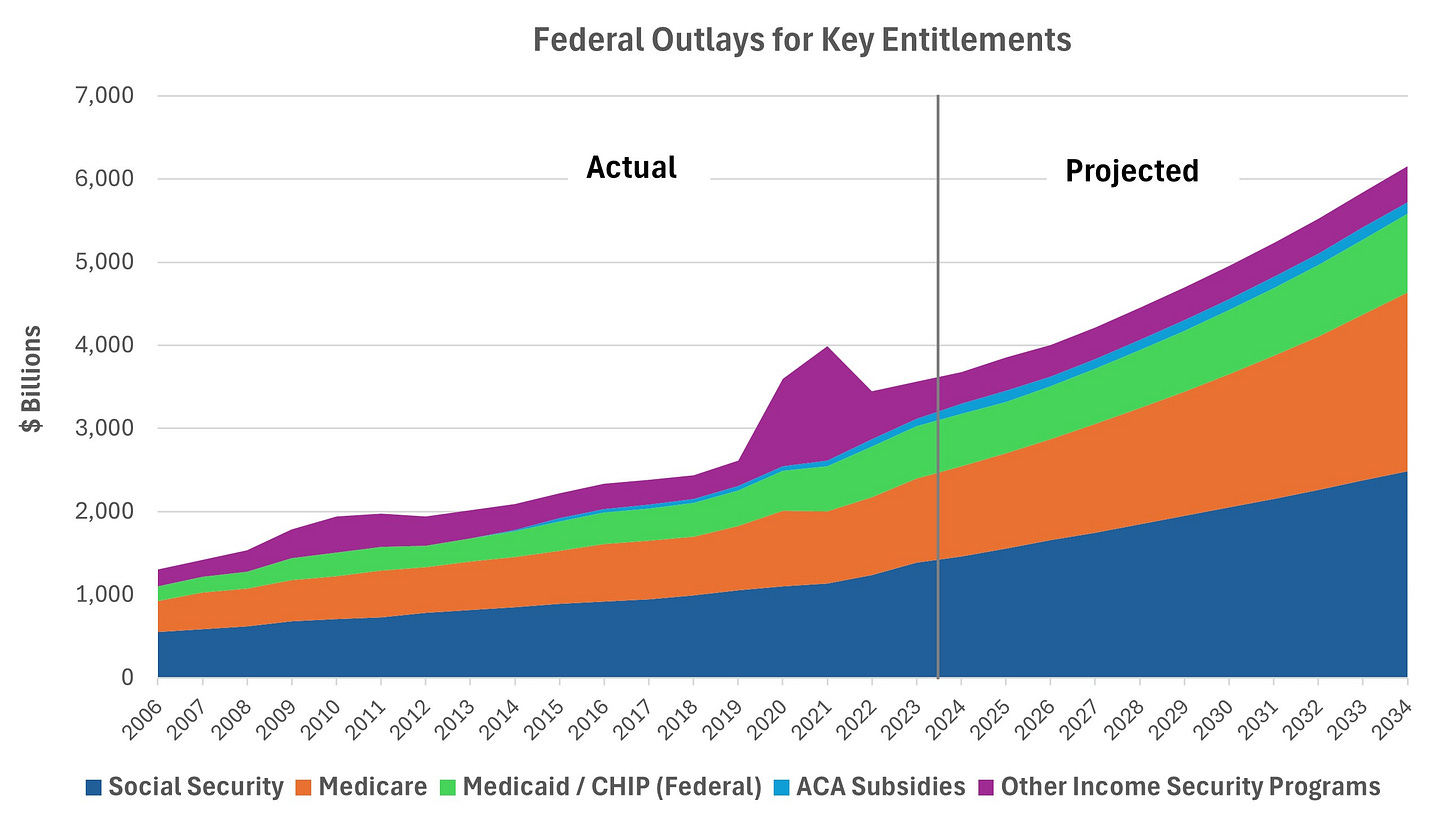

The Congressional Budget Office projects these entitlement programs will double by 2034, an alarming trend:

Why are Entitlements Growing?

Social Security and Medicare outlays are the largest entitlements and are growing the fastest, driven by demographics as baby boomers retire:

The ratio of workers to retirees in the US has declined from 42 at the end of World War II to 5 in 1960 to 2.8 today and is projected to be 2.1 by 2030. Declining workers per retiree is a problem for all the world’s advanced economies. According to OECD, half of the 20 largest economies have lower workers per retiree than the US, and three-quarters will experience greater declines over the next 30 years. These demographic changes place a larger financial burden on fewer workers, which is exacerbated by longer life spans and a higher disease burden. John Cogan of the Hoover Institution at Stanford has been one of the loudest voices ringing alarm bells about affordability of this trend and its impact on intergenerational wealth transfer in his book, The High Cost of Good Intentions, as well as numerous articles.

Impacts on Budget Deficits

But which entitlement programs pose the greatest risk to our federal budget? The answer to this question is slightly different:

In 2023, Social Security’s payroll and benefit taxes reduced its impact on the deficit by 97%, and Medicare’s taxes and Part B premiums reduced its impact by 55%. The net cost of Medicare to general revenues in 2023 was $180 billion less than the net cost of Medicaid, and despite an aging population, Medicare won’t catch up with Medicaid for a decade.

But, CBO’s projections may be overstated, as suggested by the following chart:

When adjusted for the number of people 65 or over and inflation (CPI), the growth of both OASI and Medicare costs (outlays + administrative costs) has been modest. (This is remarkable for Medicare, which has had to absorb medical cost inflation 1-2 percentage points higher than CPI.) Yet CBO is projecting significantly higher growth in inflation-adjusted per capita costs for both programs through 2034.

Funding the Deficit

While CBO projections may be exaggerated, because of demographics, the deficit in both entitlement programs is real and bound to grow. One approach to funding growing deficits in Social Security is to raise the maximum wages subject to the payroll tax. On the other hand, President-elect Trump has advocated eliminating taxes on Social Security benefits, which would have the opposite effect.

For Medicare, there is a question of mission. Medicare was originally enacted to improve OASDI by redistributing funds from working people to retirees, just as Medicaid was enacted to improve federal - state assistance programs to poor people. Medicare wasn’t originally intended as another vehicle for redistributing funds to the poor. Nonetheless, in 2003 taxes were imposed on higher income individuals and families as a progressive way to reduce the Medicare deficit (Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount or IRMAA). Making Medicare even more progressive by increasing IRMAA taxes or imposing means testing on benefits would push it further into second-level income redistribution (i.e., redistributing after-tax income). Medicaid and the ACA subsidies are funded almost entirely from general funds, and both are growing rapidly. Do we really need Medicare to follow the same path?

Part II of this post on Entitlement Economics will examine the financial impacts of Social Security and Medicare on different groups of Americans and recount a counterfactual fairy tale.

Excellent as always. Happy New Years, Dave.